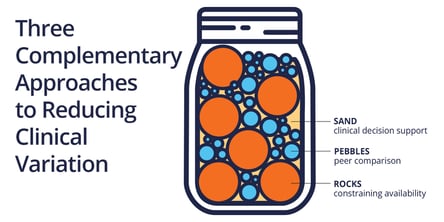

THE ROCKS, PEBBLES, AND SAND OF REDUCING CLINICAL VARIATION

- Andrew Trees

- 01/6/2022

You have probably heard the story where a professor gets up in front of the class with a large jar. The story involves putting large rocks in the jar and then asking the students, “Is the jar full?” They say, “Yes.” He then adds some pebbles to the jar to fill in the spaces and then he asks, “Is it full now?” They say, “Yes.” And then he proceeds to add sand and perhaps even water.*

The moral of the story is to prioritize the most important things in life. With a few tweaks, we can repurpose this story as we consider the various approaches to tackling clinical variation. Stick with me and I will explain.

The big rocks of clinical variation — constraining availability

The lesson in the original story is that we need to put our big rocks in the jar first — the most important. In the case of clinical variation, many organizations consider constraining availability to be the largest financial opportunity. They fill the jar of clinical variation reduction with large rocks, such as limiting drug options to generics when clinically equivalent or reducing the number of physician preference items available. Removing options, or designating options based on value, is one of the quickest and most efficient ways to reduce clinical variation. (Note: I said efficient, not necessarily effective, as I will mention later.)

The sand of clinical variation — clinical decision support

One challenge of the big rock approach is that it may miss the nuance of an individual patient’s care needs. Respecting both provider autonomy and the unanticipatable diversity of cases, many organizations quickly add clinical decision support (CDS) systems when they are looking to reduce clinical variation. They pour the sand of CDS in: offering physicians advice (not mandates or prohibitions) on how to best care for a given patient in real-time during care delivery, particularly with an eye for some low-value care to be avoided (e.g., a duplicative or unwarranted test).

Even when decision support systems are clinically accurate, some physicians find the alerts and recommendations intrusive. Still other physicians have strong feelings about the pretext of guidance from an algorithm they feel is challenging or second-guessing their skills. “Are you sure you want to order that MRI?” “Yes, in fact,” ponders the physician, “why do you think I ordered it? This patient needs it.” Just another annoying click. And what happens in those edge cases where the system is wrong? Once physicians lose trust in a system, it is extremely hard to regain that trust (and extremely expensive — usually impossible — to anticipate, program, or design away every edge case). Just ask IBM Watson.

As much as the grain of sand (i.e., a care decision) feels weighty in the moment for a physician, it is quite small in the jar. As CDS, it rarely has the time to fill empty spaces in the jar before the aforementioned issues choke it out. Even as countless pebble-sized opportunities remain.

Wait! What about the pebbles?

If you recall the story, you know that the professor warns the students about what can happen if you put the sand in before the rocks or the pebbles. You run out of room in the jar. At Agathos, we do not have strong feelings about whether, when, and how to pursue supply chain variation reduction or implement a CDS solution (we do recommend these more strongly when the choices are black and white, versus when there is any clinical “grey,” as much of medicine entails). We do, however, feel strongly that you cannot forget the pebbles.

The pebbles of clinical variation reduction — peer comparison

Agathos fills in the gaps around those big rocks with the pebbles of this story: peer comparisons that have an impressive financial impact as well as improved care outcomes. Given a panel of options, how does a cohort of peers in the same facility, managing the same patients, practice differently over many cases? These pebbles can be materialized as short, actionable texts sent once per week to physicians, showing them how their practice patterns compare to those of their peers. This approach has several advantages over the other categories in the clinical variation jar:

- This approach [of social proofing, text delivery] has wide-ranging behavioral economic evidence and leads to measurable behavior change that results in lower costs and improved outcomes. 1 2 3

- Unlike constraining options (the big rocks), this approach engages and empowers physicians to be active participants in the organizations’ efforts to reduce costs and improve patient outcomes.

- Unlike CDS (the sand), Agathos insights avoid the problem of a sample size of one, emphasize patterns (vs. right and wrong), leverage both System 1 and System 2 thinking (here’s a quick overview of Kahneman’s model), and can be reviewed at physicians’ convenience — in all facilitating a more thoughtful, holistic, and influential consideration of the data.

- This approach also builds trust and collaboration among respected peers who may perform stronger on some metrics and be willing to share their practice patterns with others. This is a critical value-add in the current healthcare climate, where any improvement to culture, reducing burnout, or enhanced camaraderie helps physician retention.

Three different, complementary approaches to reduce clinical variation

So that’s it. A quick survey of three different — and highly complementary when appropriately used — approaches healthcare organizations can take to reduce clinical variation. We are bullish on the pebbles and would enjoy the chance to show you how they might work at your organization.

Interested? Read our 5 Guiding Principles white paper to learn more about how we engage physicians with data they enjoy and actually use.

* Here’s a pretty good 2-minute video if you need a refresher on the main story referenced throughout this post.

1. Albertini et al., 2019 “Evaluation of a Peer to Peer Data Transparency Intervention for Mohs Micrographic Surgery Overuse,” JAMA Dermatology.

2. Meeker et al., 2016 “Effect of Behavioral Interventions on Inappropriate Antibiotic Prescribing Among Primary Care Practices,” JAMA.

3. Navathe et al., 2016, “Physician Peer Comparisons as a Nonfinancial Strategy to Improve the Value of Care,” JAMA.

About Author

Andrew Trees

Andrew Trees is CEO of Agathos. He has a passion for health economics, pricing and market access, evolving payment and delivery models. Prior to founding Agathos, Andrew consulted with ClearView and QuintilesIMS, researching with hundreds of physicians, payers, and administrators on matters of clinical evidence and practice economics.